Japanese News Project

I made a serverless ETL pipeline to record all the words from 65,000 Japanese news articles. Then, I found the most frequent 5,000 words and visualized them.

This post explains why I made the pipeline, how I designed it, and how it works. You can find all the code in my Github repo.

Table of contents

- Why analyze Japanese news articles?

- My project strategy

- Requirements

- Design

- Development: Finding articles

- Development: Sending articles to queue

- Development: Extracting and processing article text

- Development: Storing, aggregating, and exporting

- Results and next steps

- Conclusion

- Notes: Estimating costs

Why analyze Japanese news articles?

I wanted to make a word frequency list because it can benefit learners of the Japanese language. Personally, I enjoy reading Japanese news - it helps me learn the language in a fun, meaningful way. In the future, I’d like to use the word list to create an electronic flash card deck. Intermediate learners could use this as a bridge from beginner textbook material, as prep for reading real Japanese news articles.

Also, this project will reveal trending topics in the Japanese news cycle. For example, various words related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Olympics are very likely to appear in articles from 2020 and this year, 2021.

My project strategy

To keep my project organized, I followed the engineering design process. However, creating the data pipeline was not a linear process - my architecture evolved over time as I learned more about the strengths and weaknesses of AWS services. To make sure I actually finished the project, I just focused on making a minimum viable product. I also asked for help online when I got stuck.

Requirements

My goal was to create a word frequency list using Japanese news articles as the source data. Here’s what I needed to accomplish this:

- I needed a data source that could provide at least tens of thousands of Japanese news articles, without overwhelming the host with requests.

- I needed to avoid copyright issues when working with the news articles.

- I had to create a batch data pipeline that could tokenize the Japanese text, store it, and aggregate it.

- The project must be coded in Python, because I am most comfortable using it.

- The whole project should cost me $10 or less.

I was able to fulfill all of these requirements using existing tools. For my data source, I used Common Crawl. Common Crawl is a non-profit organization that crawls billions of web pages every month. Their data is freely accessible to the public in an S3 bucket, so I can access a large amount of data with few restrictions. For students wanting to build their own datasets for projects, I highly recommend using Common Crawl.

Also, I confirmed that using Japanese news articles for my project is perfectly legal. Articles 30-4 (第三十条の四) and 47-7 (第四十七条の七) of Japan’s Copyright Act preserve my right to collect this data for non-commercial information analysis.

For my batch data pipeline, I had to tokenize Japanese text. “Tokenizing” a sentence means breaking it into individual words. Unlike in English, Japanese text doesn’t separate words by spaces, and other features of the language complicate things further.

Here’s an example:

日本語には多様な方言がみられ、それらはいくつかの方言圏にまとめることができる。

(Translation: “Japanese has a variety of local dialects, which can be categorized into several regional groups.”) Source

Thankfully, an open source Python library called SudachiPy can be used to tokenize Japanese.

Finally, AWS has generous free tier pricing for many popular services. I used AWS to create my data pipeline, with the boto3 library for Python to make API calls to AWS services.

Design

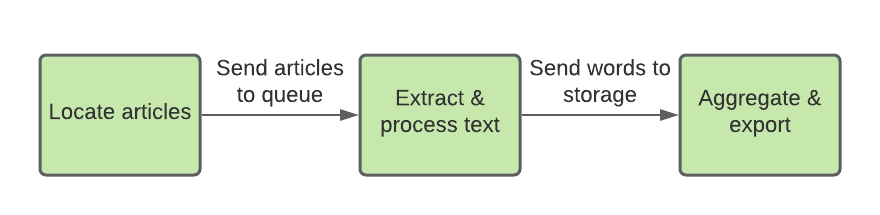

I needed a batch data pipeline that worked like this:

While considering my architecture, I tried to stay open-minded and consider the trade-offs of various options. I also made a post on a data engineering message board with an early design proposal, where I got lots of helpful feedback and ideas. Eventually, I decided to adopt a serverless approach for my batch data pipeline, due to its scalability and low cost.

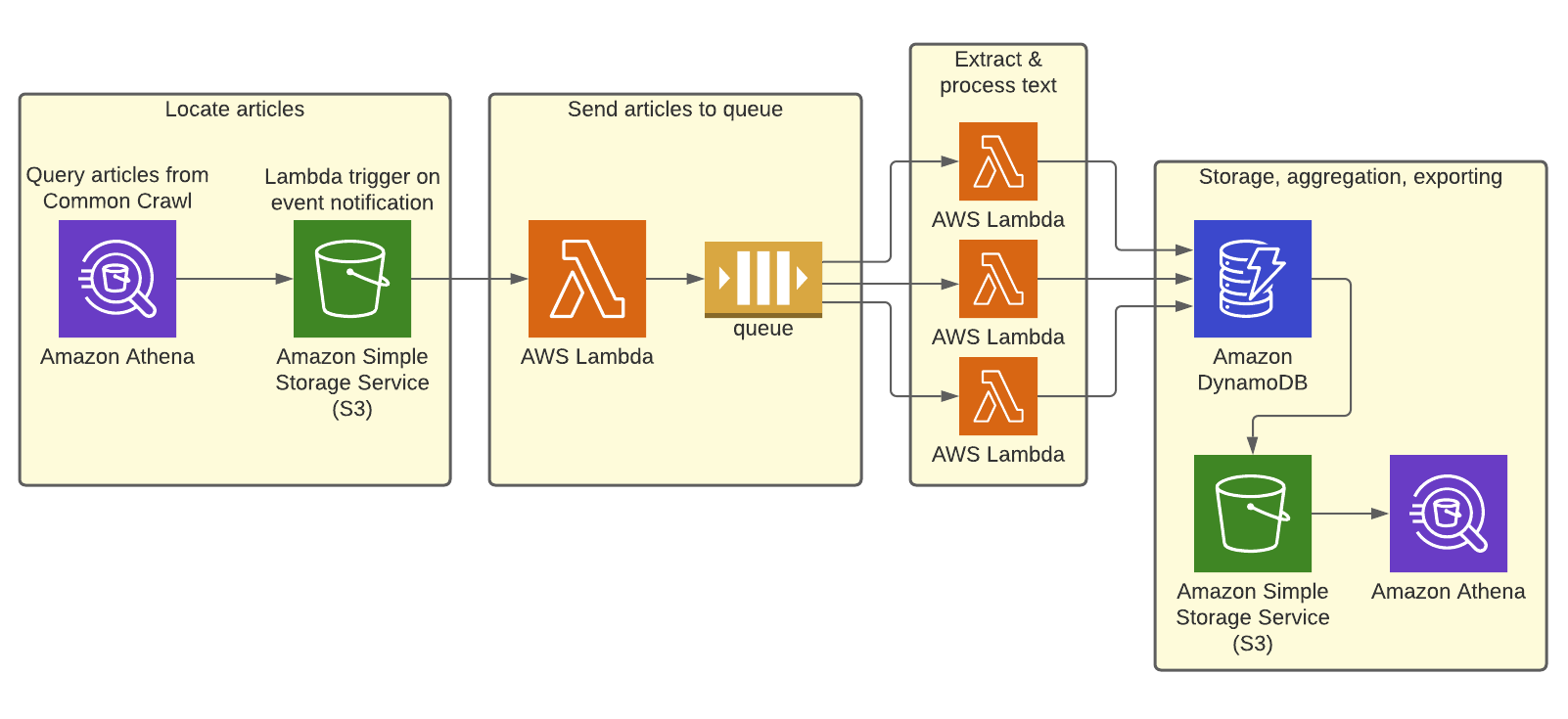

To start, I could use Athena to query Common Crawl for news articles, and then shuttle that data to a processing service via SQS. I needed to process a large number of fairly short articles, so I chose AWS Lambda for its concurrency, quick init time, and low cost. With Lambda, I’d also need to use a database to handle a large number of concurrent writes to the data store.

I considered two database services: RDS and DynamoDB.

Pros and cons of RDS:

- Pro: I could run a SQL database. This would make it easy to perform aggregations.

- Con: I’d need to configure my database to handle throughput. This requires quite a bit of troubleshooting.

Pros and cons of DynamoDB:

- Pro: I could easily provision for nearly any amount of throughput, and also use auto-scaling and burst capacity if needed.

- Con: Unlike RDS, DynamoDB doesn’t support aggregations because it’s a NoSQL database.

I chose DynamoDB because its serverless nature allows me to easily scale to high throughput. Though it doesn’t support aggregation, there are some workarounds (for example, using DynamoDB Streams with a second table). Ultimately though, I decided to store un-aggregated words and counts in a DynamoDB table, then export the data to S3. From there, I’d aggregate it with Athena to get my final results.

Doing a data export makes this solution hard to scale - it would be costly and slow for a larger sample of articles. But, I chose to do this anyway because my project is a small, one-time batch job. If I had to redo this project from scratch, I’d try to find a way to use RDS and send larger batches of data to the tables.

Here’s my finalized setup:

This setup fulfills all the requirements for my small project, and ultimately got the job done for less than $1 in total. For larger, more expensive workloads (i.e., several million articles), I’d definitely consider using AWS Batch to do extraction and tokenization, with storage in RDS.

Development: Finding articles

The data pipeline begins with a query, which locates Japanese news articles in Common Crawl. I chose to take articles from Yahoo News Japan because of its varied content, large number of articles, and the uniform URL format of articles. The majority of articles are free, and paywalled articles give a preview with at least a hundred characters of text. To me, this means all articles are useful for analysis.

Each crawl in the Common Crawl bucket contains numerous files in compressed WET and WARC formats. WET files hold metadata on crawled pages, while WARC files hold text data from pages. Using Athena, I registered Common Crawl as a database table, then queried the WARC files for a recent crawl. With my query, I could find the locations of distinct Yahoo News Japan articles stored there.

Here’s my test query:

I decided to take my articles from crawls between February 2020 and May 2021. My finalized query found all Yahoo News Japan articles from each partition, pooled the results using UNION statements, and finally took a random sample from those articles. You can view that query here.

Development: Sending articles to queue

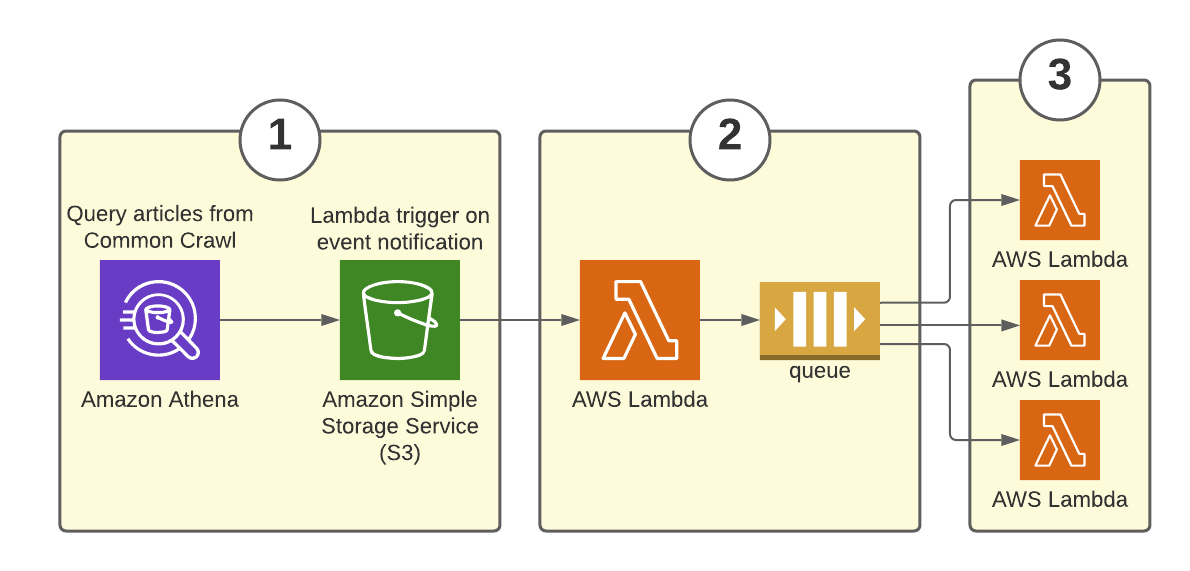

Before I could process the articles, I needed to send their info to the processing service. I created a fan-out pattern using SQS and Lambda to utilize Lambda’s concurrency:

- Athena writes a CSV file of queried articles to an S3 bucket I own.

- When this occurs, S3 sends an event notification to a queueing Lambda (called s3_lambda_sqs). The notification triggers the Lambda to read the CSV file, and send the content of each row as a message to an SQS standard queue.

- A Lambda function (called queue_consumer) concurrently removes batches of messages from the queue and processes articles.

I chose to process 65,000 articles total so that my first Lambda function wouldn’t time out while it was enqueueing messages. I could have used EC2 or some trick with Lambda to enqueue more articles, but it was important for me to move on and get a prototype working first. View the queueing Lambda code here.

Development: Extracting and processing article text

Each queue message contains the WARC filename, byte offset, and record length for a distinct article. The Lambda function consumes a batch of up to 10 queue messages, then does the following for each message:

- Use the WARC filename, byte offset, and record length to do a byte-range request on the commoncrawl bucket. This grabs the web page’s text data without needing to download the entire WARC file.

- Selectively parse the page contents with bs4. The news article text is always contained within the page’s

<article>HTML tag, so remove any text data that is not part of the article itself (i.e., “recommended article” links, ads, etc.). - Use the Japanese tokenizer SudachiPy to break the article text into individual words, and add those words to the pool of all unique words gathered so far.

Then, once all articles have been tokenized, write each word to the DynamoDB table. You can view the queue_consumer code here.

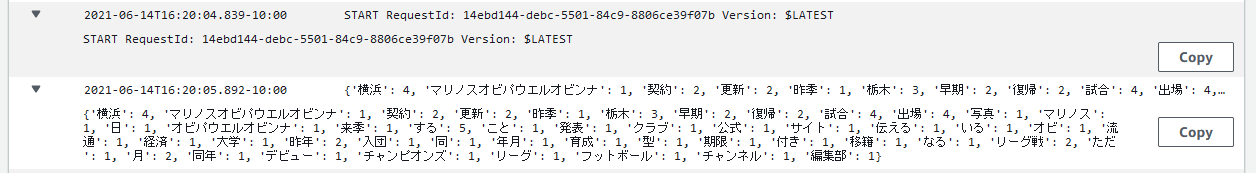

Here are an example article’s tokens, as shown in CloudWatch Logs:

For my tokenizer SudachiPy to work, Python needed the sudachipy library, plus a dictionary. The dictionary is 250 MB, so I had to bundle all Lambda code and dependencies in a Docker image.

My image included wheel files to compile SudachiPy’s Cython code, so I tried to reduce the image size using a multi-stage build. I couldn’t figure out how to do it though, so the image ended up being 488 MB (with a 5 second init time in Lambda).

Development: Storing, aggregating, and exporting

Storing words

I decided to use 19 concurrent Lambda instances for queue_consumer, for 969 WCU of provisioned capacity. Though this number had a meaning in older designs, it ended up being arbitrary in my finalized design.

Using the DynamoDB cost calculator, I then estimated that the total cost of the batch job would be roughly $3.10 - see the Notes section for the calculations. Time to start the batch job!

I created a table called word_storage, with uuid as the partition key. The queue_consumer Lambda writes all words to this table. I then provisioned 969 WCU and 1 RCU to the table, and ran the 65,000 article query in Athena. When the batch job finished, I reduced the WCU to 1 to save money. There were no errors, throttling, or Lambda timeouts when I searched Cloudwatch.

Here’s part of a processed article batch:

Aggregating and exporting words

At this point, my word_storage table contained 7,253,029 items, and the table size was 426.4 MB. Now, I needed to aggregate and export my data.

I deactivated the S3 event notification and exported the table to S3. The table arrived in compressed DynamoDB JSON format. Here, items are nested structs separated by newlines. Here’s an example item:

{"Item":{"uuid":{"S":"a422fdb4-b849-42bf-8d46-b0a4f861a19d"},"count":{"N":"1"},"word":{"S":"配慮"}}}

I had to register the table schema before I could query. Then, I ran the aggregation query.

This stored the top 5,000 most frequently appearing words and their counts in S3. The results looked good, so the project was finished!

Results and next steps

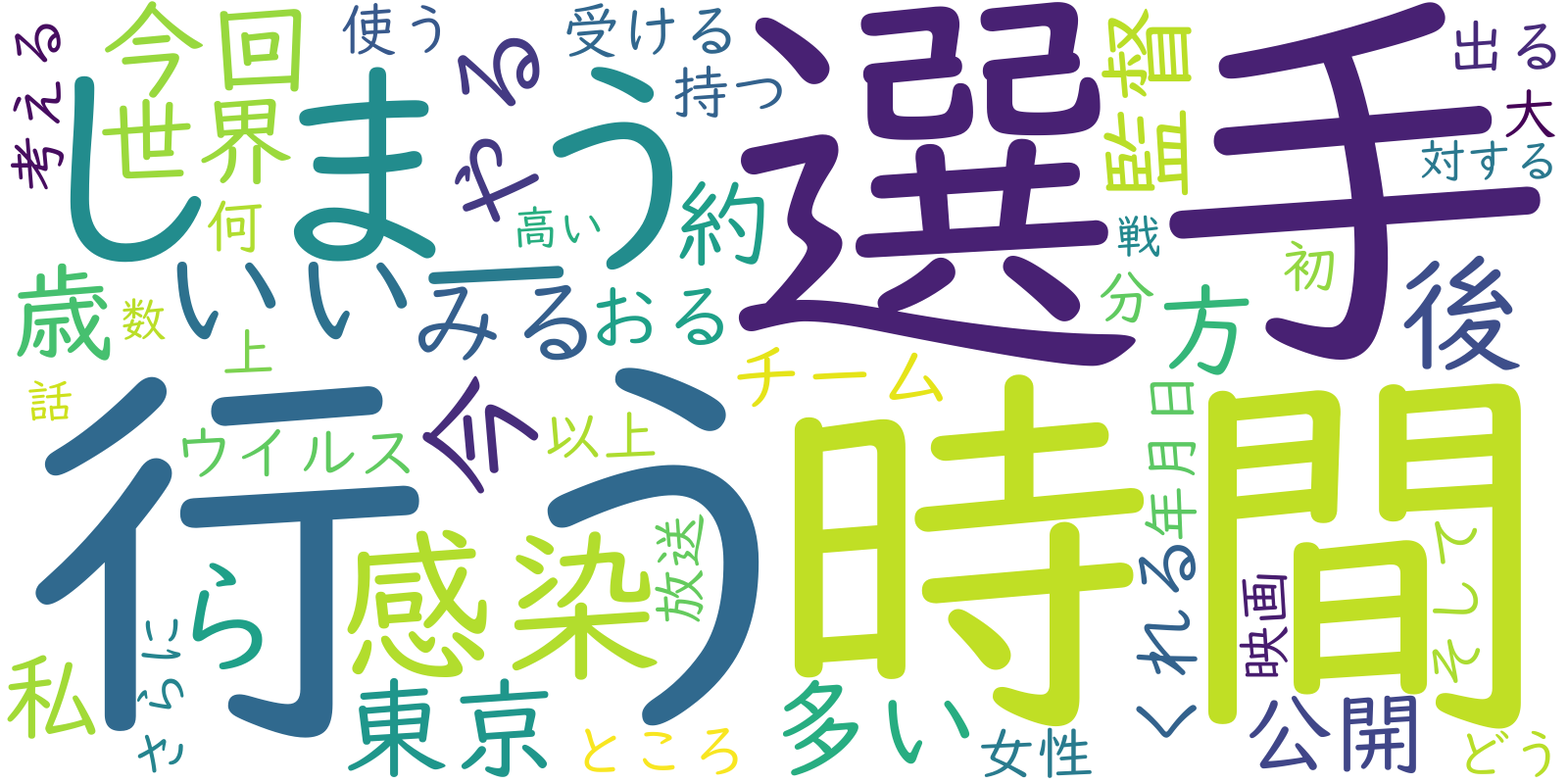

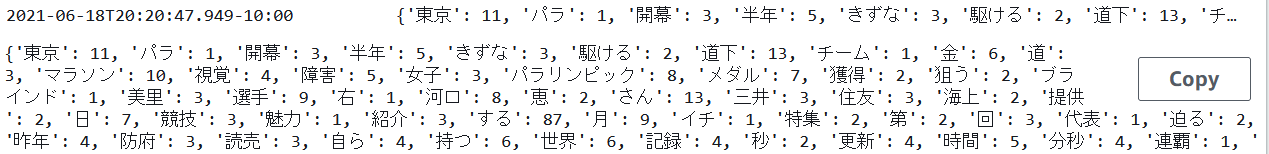

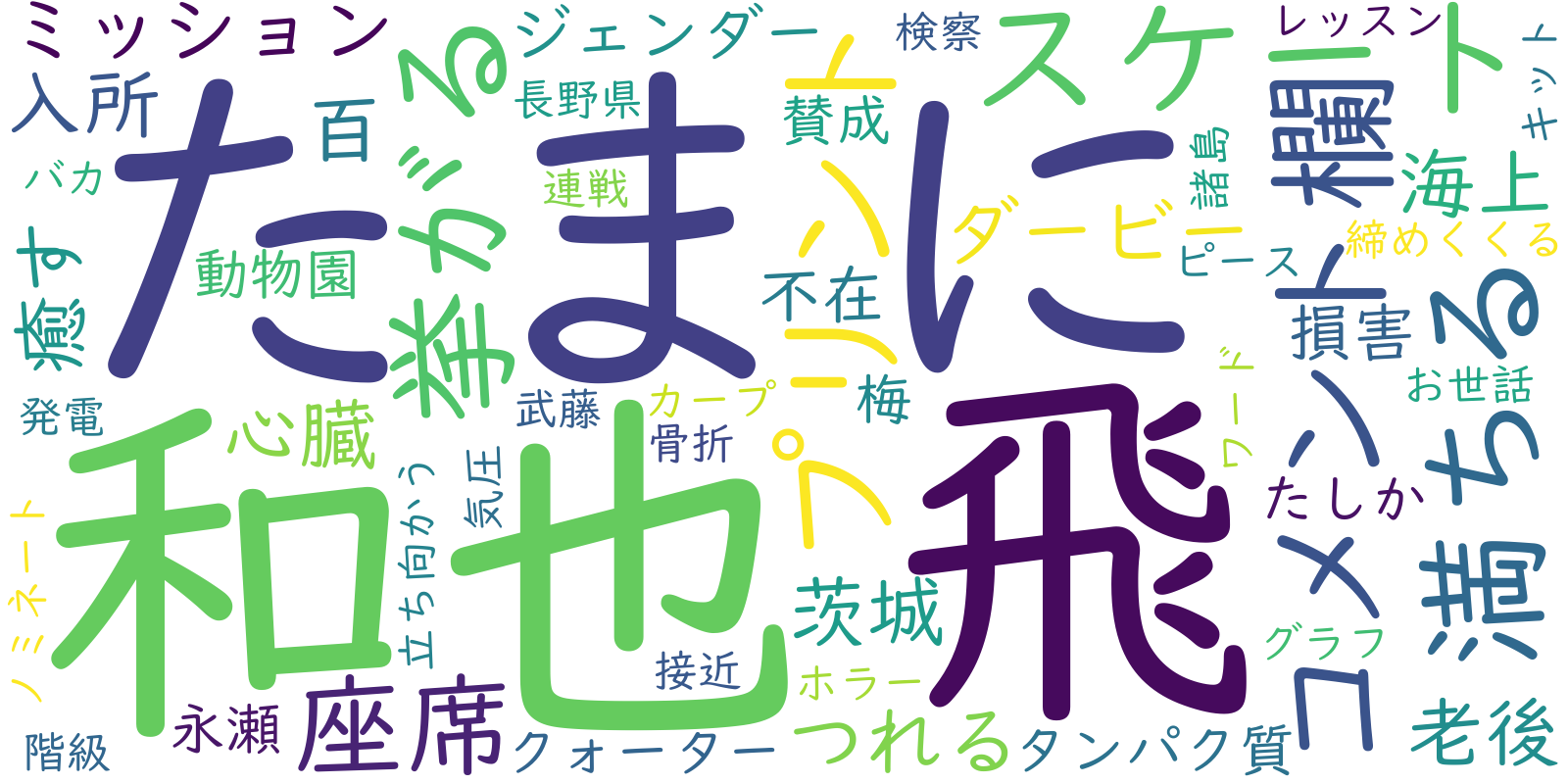

For fun, here is a word cloud showing the top 50 most frequent words in the list:

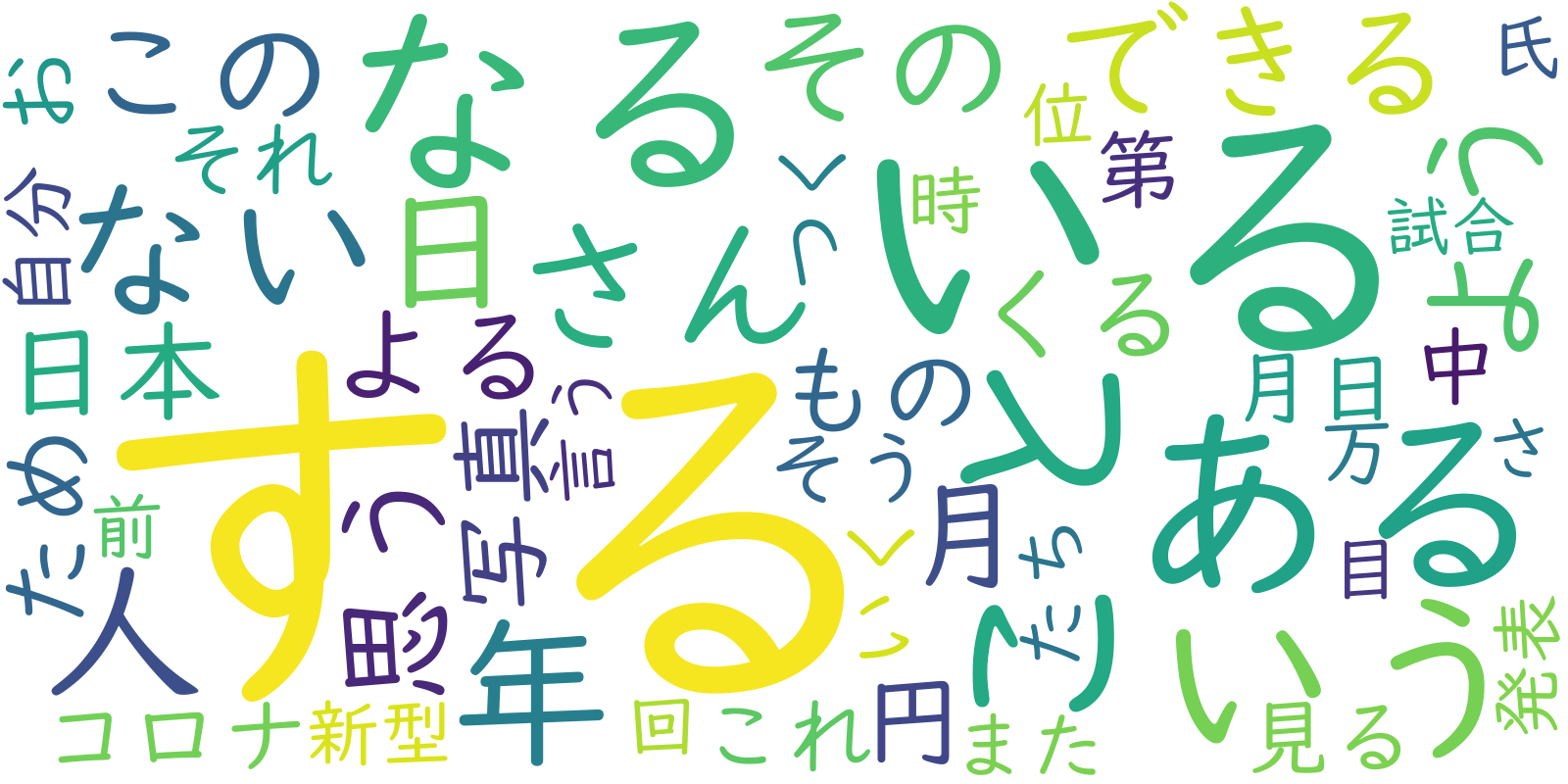

And words 50-100:

And the last fifty words, from 4950th place to 5000th place:

(View my code for generating the word clouds here!)

The most frequently appearing word in the list was する (meaning “to do”), with 731,473 appearances. One common word for COVID-19, コロナ, was the 26th most common word, with 32,798 appearances. Three more pandemic-related words made it into the top 100:

- 新型 (the “novel” in novel coronavirus) at 45th place,

- 感染 (meaning “infection”) at 56th place,

- ウイルス (meaning “virus”) at 77th place.

Interestingly, many sports-related words occurred within the top 100, possibly due to Olympics-related coverage. You can find the complete word list in my Github repo.

The total cost of the project, including all services used for testing, was 86 cents. I’m very satisfied that the project cost less than a dollar! My DynamoDB usage cost 4 cents, and data transfer was $0. I was billed $0.60 for using EC2 - I temporarily left my Docker images in Cloud9, and got charged for storage until I moved them to ECR. Generally though, free tier gave me lots of wiggle room for testing things.

Two things I’d like to try next time:

- Use AWS Batch to process millions of articles

- Redo the project using CloudFormation or Terraform to make setup and extensibility easier. Also, use AWS’s serverless application model (SAM) to test Lambda code locally

Conclusion

I learned so much by doing this project. I got hands-on experience working with many AWS services, used Docker for the first time, and got acquainted with NoSQL. I also learned the importance of following a good design process, thinking flexibly, and asking for help. I look forward to learning and building more!

Notes: Estimating costs

Besides Athena, my use of all other services (S3, Lambda, SQS) was within the free tier quota. Athena queries the Common Crawl bucket efficiently, using the columnar format and searching only WARC files. I expected the Athena query to cost about $1 at maximum. The biggest cost was likely to come from DynamoDB.

As an experiment, I created a test table and provisioned 100 WCU and 1 RCU for it. Then, I ran a 30-article query to estimate the WCU needed and the general duration of a queue_consumer Lambda function. This info was gathered directly from Cloudwatch Logs. Note that concurrency was disabled for this experiment.

In my experiment, Every Lambda call had a write rate of roughly 51 writes per second. This means that 51 WCU are needed per concurrent Lambda on average to prevent throttling on the table. I wanted to use 19 concurrent Lambda instances for queue_consumer, so in total, this requires 51*19 = 969 WCU.

On average it took queue_consumer 3.29 seconds to fully process a single article. Since I set a batch window of 1 second, most concurrent instances should take 10 articles. So based on this average, a single instance would take 32.90 seconds to process 10 articles. That’s 190 articles every 32.90 seconds = 5.77 articles per second.

If I want to process 65,000 articles, that will take 65,000 articles / 5.77 articles per second = 11,265.16 seconds = 3.13 hours.

Plugging 969 WCU (provisioned capacity) into the DynamoDB price calculator:

- I’ll estimate the monthly data storage size is 1 GB. A data export of 1 GB to S3 will cost $0.10 per month. I’ll only do this once, so the overall cost of the export will be around $0.10.

- If the average item size is 0.25 KB, storage will cost $0.25 per month - once the data transfer to S3 is complete, I might delete this table afterwards to save money.

- I’ll assume the baseline write rate and peak write rate are the same at 969 WCU (and no auto-scaling needed). The data storage and provisioned capacity would cost $460.13 per month. Provisioned throughput capacity is billed on an hourly basis. So, if I reduce WCU to 1 once the batch job finishes, costs will be incurred only for the duration of the batch job (3.13 hours).

- Finding the hourly cost for using this provisioned capacity and data storage: $460.13 per month / 30 days = $15.34 per day / 24 hours = $0.64 per hour.

- Since the batch job will run for approximately 3.13 hours, the total DynamoDB usage cost should be around $0.64 per hour * 3.13 hours = $2. Adding in the cost of data export, this is $2.10.

In total, I estimated that using DynamoDB for this project should cost approximately $2.10. If the Athena queries cost $1, the project should cost roughly $3.10 in total. This was well within my $10 budget. Additionally, free tier would reduce the DynamoDB cost.

Ultimately, the total cost of services ended up being 86 cents, including testing. The batch job finished in 3 hours and 6 minutes, consuming roughly 670 WCU on average according to Cloudwatch. With more concurrent Lambda instances and provisioned WCU, the job may have finished even quicker.